LaQuinton Ross sent Ohio State to the Elite Eight with a three pointer against Arizona. Just type his name into Google and you can pick from tons of articles that tell you that. However, Ross was involved in an equally as crucial three pointer that played a tremendous role in sending Wichita State to the Final Four. Ross' shot may have gotten the attention of the media, but his defense went virtually unnoticed (to my knowledge).

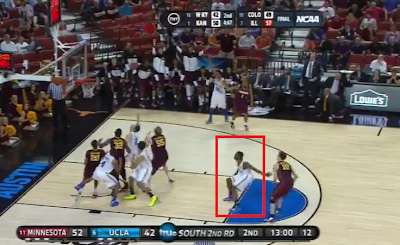

With 2:30 left in the game, Ohio State had nearly completed their comeback. Wichita State was up three and had the ball. Ohio State was really one stop away from getting in great position to win the game. Wichita State broke the pressure and with 17 seconds left on the shot clock had the ball pulled out:

In the photo above, you can see the start to Wichita State's high pick and roll. Ross is circled and at this point is in reasonable guarding position on Tekele Cotton considering the context of the play.

Continuing on with the play, off of the pick and roll Ross does the right thing by sinking into the lane. It looks like he had the defensive assignment of showing on the roll man. His job is to be in a position where he can make the pass to the roller difficult while also being able to close out on his actual man. At this point in the play (above), Ross is in position to do just that.

The pick and roll ultimately proves unsuccessful for Wichita State. Ohio State switched the screen and Deshaun Thomas winds up guarding Fred Van Vleet (the ball handler). It appears that Wichita State is content with simply spreading the floor and letting Van Vleet create as the shot clock winds down. However, before Van Vleet looks to make his move, this happens:

Maybe somebody reading this can shed light on what exactly Ross is doing in the GIF above. The pick and roll is over, so he should be closer to the passing lane between Van Vleet and Cotton. He points at a screen occurring behind him and then right after points at his man (Cotton). I think he just got mentally lost on the floor and pointed at Cotton only to realize at the last second that was his man.

The point here is not that Ross is a bad defender. Obviously this one play does not define Ross as a defender or as a player in general. The real point is the focus on offense over defense. In my opinion, Ross' defensive blunder was just as important as his offensive heroics. However, the two plays were not treated close to equally in the analysis of Ohio State's weekend performance.

Sunday, March 31, 2013

A Few Parting Thoughts on FGCU

Florida Gulf Coast University captivated the nation en route to being the first ever 15 seed to go to the Sweet 16. A conversation I had a while back with Iona College assistant coach Zak Boisvert, piqued my interest in wanting to look into the numbers about tempo and its effect on win percentage. In other words, if the game tempo is closer to your pace than your opponents do you have a better chance to win? I thought Florida Gulf Coast would be a great case study.

In games where the tempo was played closer to Florida Gulf Coast's style than their opponents, they went 9-1 on the year. In games where the pace was closer to their opponents than their own, they went 8-4. When the opponent had a pace very similar to FGCU, they went 7-6. As the chart indicates FGCU sped teams up to a faster pace than they averaged in both wins and losses. This shows no evidence for the basketball cliche that controlling tempo wins games.

I was just perusing through their numbers, and also found their turnover discrepancy interesting. It likely is this way for most teams, but FGCU had an 19.0 turnover percentage in wins, and a 25.2 turnover percentage in losses. They went 1-5 this year in games where they had a turnover percentage of 25 or higher.

Regardless, it was an awesome run and one that I will most definitely be telling my kids about. With three 15 seeds winning first round games the past two years and one getting to the Sweet 16, maybe next year is the year we see a 16 seed beat a 1 seed.

In games where the tempo was played closer to Florida Gulf Coast's style than their opponents, they went 9-1 on the year. In games where the pace was closer to their opponents than their own, they went 8-4. When the opponent had a pace very similar to FGCU, they went 7-6. As the chart indicates FGCU sped teams up to a faster pace than they averaged in both wins and losses. This shows no evidence for the basketball cliche that controlling tempo wins games.

Regardless, it was an awesome run and one that I will most definitely be telling my kids about. With three 15 seeds winning first round games the past two years and one getting to the Sweet 16, maybe next year is the year we see a 16 seed beat a 1 seed.

Friday, March 29, 2013

Davante Gardner: Zone Buster

Syracuse's 2-3 zone last night looked invincible versus the number one offense in the country. Indiana had scored more points per possession than their opponents (on average) give up in every game this season until Temple and Syracuse. Syracuse's defensive dominance had people wondering why a team would play anything other than zone. I went back and looked at Syracuse's defensive performances throughout the season. Sure enough, their worst of the year (allowing 1.21 points per possession) came to none other than Marquette.

It seems like a no-brainer to zone Marquette. Buzz Williams' squad is having one of the best offensive seasons ever for a team that shoots the three ball so poorly. Marquette ranks 19th in offensive efficiency in the nation despite shooting just 30.5% from three on the season. In theory, a 2-3 zone forces an offense to make deep shots. Marquette doesn't have the personnel to consistently knock down threes, but they do have Davante Gardner. Gardner is one of the most unique big men in the country. He is listed at 290 pounds, shoots 84.4% from the foul line, and can euro step. He also just happened to have his best performance of the season against the Orange in February.

Gardner went a perfect 7-7 from the field and went 12-13 from the foul line against Cuse the first time around. He also had just one turnover and four offensive rebounds. Gardner is a zone killer in the paint. His big body and nice touch disrupt what the Orange try to do defensively. First, let's look at the most obvious impact Gardner has against the zone: Occupying space.

In the photo above Gardner seals his man and clears out the lane. The result of this play was actually a basket for Jamil Wilson (the other guy posting up down low). Gardner constantly makes contact with the zone, clearing space in the process for others to work.

The following is a look at the three ways Davante Gardner is a zone buster:

1. Inside Finishing

If you want to know about Syracuse's shot blocking abilities, just ask Cody Zeller. Last night nothing came easy for Zeller and Indiana. However, Gardner is effective in a much different manner. He doesn't rely on athleticism as much as strength and a great touch. When Gardner got the ball down low against the zone, he used his body to prevent being blocked and to get to the foul line.

2. Offensive Rebounding

The zone is notoriously susceptible to second chance opportunities. Gardner is 89th in the country in offensive rebounding percentage. In the first meeting, he got four offensive rebounds from his positioning and strength. Maybe the most important aspect of his offensive rebounds is the ensuing put back. Gardner was able to clear space and get easy baskets down low off Marquette misses.

3. Foul Line Jumper

In the high post, Gardner forces Syracuse to respect his foul line jump shot. I found four plays where Gardner's ability to either force the zone extend or knock down a jump shot led to Marquette points. The first play the zone extends and Gardner hits the open man down low. The second play Gardner starts at the high post and cuts down the lane during a baseline drive for an easy lay-up. Finally, the last two plays Syracuse doesn't get out far enough and Gardner hits both a floater and a jumper.

Marquette doesn't need a great three point shooting performance to advance to the Final Four. In the first meeting, Marquette shot just 5-21 from three and yet still posted the best points per possession total of any Syracuse opponent this season. Gardner is the straw the stirs the drink against the zone for the Golden Eagles.

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Indiana's Weakness

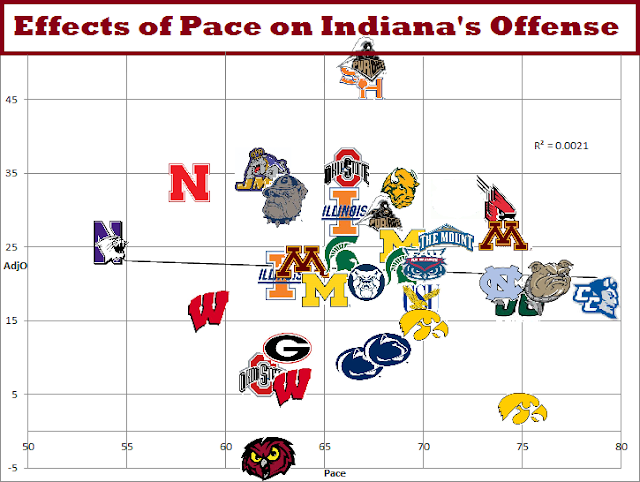

If you were to force me to pick a team I think is going to win it all, I would likely take Indiana. On the Sweet 16 efficiency graph, the Hoosiers have the best offense of anyone and an average defense (relative to the other 15 teams). C.J. Moore pointed out recently that the Hoosiers' weakness is playing at a slow pace. Moore noted that Indiana's record is bad in games with 64 possessions or less.

I am naturally pretty skeptical of change in pace being a big factor in a team's success. Ty Lawson's UNC team from a while back is the prime example. They played at a tremendous pace, but were equally as deadly in the half court (contrary to popular opinion). Great teams tend to be great, pretty much regardless of pace. To examine Indiana, I wanted to go beyond simply looking at their record by pace. Instead, I looked at the effect of pace on offensive efficiency and defensive efficiency. I wanted to make sure to account for strength of schedule. To do this I calculated AdjO and AdjD for each game as:

AdjO = (Indiana's Game Points Per 100 Possessions) - (Opponent's Average AdjD)

AdjD = (Opponent's Average AdjO) - (Indiana Opponent's Game Points Per 100 Possessions)

Note: Higher numbers are a good thing for Indiana for BOTH AdjO and AdjD

Note: Higher numbers are a good thing for Indiana for BOTH AdjO and AdjD

The highlighted portion of the table shows the culprit of Indiana's struggles. In games with under 65 possessions, the Hoosiers are fine offensively but have been much worse defensively. This is probably an unexpected finding, but I think there are some reasonable explanations. First, I didn't think for a second that Indiana would be a worse offensive team in slow paced games. The Hoosiers have the number one offense in the country. The number one offense in the country isn't likely to have any big weakness. Regardless of the pace of game, Indiana can score the basketball. Still, the question remains: why does Indiana's defense struggle in slow paced games?

The convenient answer is to blame it on Jordan Hulls. He has been perceived as Indiana's defensive weakness for most of the season. This very well might be a part of it. In the half court, opponents may be able to expose Hulls as an on ball defender. Maybe a better reason is Indiana's defensive style. The Hoosiers don't let their opponents get good looks and don't foul. They are 18th in the country in opponent eFG% and 14th in the country in opponent FTRate. However, they are very average when it comes to rebounding (152 in DR%) and turning teams over (120 in TO%). I suspect that these defensive shortcomings are more exposed in a grind it out, slow paced game.

The following shows the effects of pace on Indiana in graphical form:

As you can see, Indiana's round of 32 game was an exception to their season performance. Indiana was very good defensively on Sunday, but scored fewer points per possession than their opponent's defensive average for the first time all season. The thing that might stand out most to me from these graphs is Indiana's defense against faster paced teams. In games over 70 possessions, Indiana's defense has been great. Like I said before, IU's offense is great regardless of pace. So in uptempo games, it's going to be very difficult to beat the Hoosiers.

Monday, March 25, 2013

Visualizing the Sweet 16

The following is a visualization of the teams and top players remaining in the Sweet 16. All statistics are full season averages (the last two games included):

1. Adjusted efficiency of remaining teams per kenpom.com

2. Adjusted tempo of remaining teams per kenpom.com

3. The offensive and defensive four factors of all 16 teams. These are NOT schedule adjusted. (Click to enlarge)

4. The top players remaining by efficiency and by usage/volume. Note: numbers are not adjusted for schedule

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Shabazz's Rebounding

Shabazz Muhammad's season ended on Friday at the hands of Minnesota. The Bruins had two big things working against them: the injury to Jordan Adams and the task of keeping Minnesota off the boards. The Golden Gophers are first in the country in offensive rebound percentage, grabbing 44% of their missed shots. On the other hand, UCLA has struggled all season long with rebounding. They rank 206th in the country in offensive rebounding and 264th in the country in defensive rebounding. At 6'6", Shabazz's personal OReb% was a solid 9.9%, but his DReb% was an awful 8.5%. To put that into perspective, Gonzaga's 5'11" David Stockton's was higher this season (9.2%).

Trying to keep Minnesota off the offensive glass had to have been a main priority for Ben Howland on Friday. The Bruins as a whole actually did a pretty good job of this. Minnesota had 10 offensive rebounds (32.4% OReb%, well below their season average). Still, if you look at the box score you will see that Shabazz had ZERO defensive rebounds in 39 minutes. That's actually pretty hard to do, you would think a ball is going to fall in your lap at some point in the game.

How does an athletic 6'6" forward not get a single defensive rebound in 39 minutes? Well to answer that question I decided to go back and look at the film. Of Minnesota's 10 offensive rebounds, Shabazz was on the court for nine of them. The photos below highlight where Shabazz was on the court when Minnesota got their nine rebounds.

1. In good position but flat footed, spectating

For Shabazz's sake, I was hoping the reason for his lack of rebounding was to leak out in transition. Although this might not be an optimal strategy, it would mean there is at least an advantage to his lack of rebounding. Otherwise, Shabazz is simply very bad at the skills involved in rebounding or not hustling (or both). This first attempt shows a flat footed Shabazz under the hoop. In his defense, he has three UCLA teammates in the paint with him.

2. Boxing out

The problem with this analysis is we can't be sure of Howland's gameplan. Basketball purists are quick to teach the box out, but the fact is that's much easier said than done against Minnesota. Still, I think it's safe to say that Shabazz did a pretty good job on this possession

3. Late getting back in transition

Here Minnesota got an easy put back in transition off of Shabazz's miss on the other end. He was very late getting back, but we're not too concerned about this one in terms of rebounding ability.

4. Sort of boxing out the shooter

Shabazz was guarding the initial shooter on this one. He didn't box out immediately, but at least tried to recover after he realized the ball wasn't going in.

5. Flat footed, spectating

The ball doesn't go to Shabazz's side, but he is still pretty much just standing and watching the play unfold. This is an example of the worst scenario for Shabazz. There are obviously very few times in a basketball game where standing and watching isn't a bad thing.

6. Elevating for the rebound

Shabazz gets his hand on this ball, but was not able to come up with it. The ball got batted out for a long rebound. By getting his hand on the ball, he may have prevented an easy layup for Minnesota (even though they were still able to maintain possession).

7. Flat footed, spectating

Another negative play for Shabazz. He's not boxing out or going after the ball. He's not even leaking out, he's just standing and watching.

8. In good position but flat footed, spectating

More of the same here.

9. A bit more of pursuit

Shabazz took steps towards the basket to potentially grab a rebound, but the ball bounced off the rim hard. You can see in the photo he is changing his momentum to either try to continue to pursue the ball or possibly to leak out.

Obviously, this analysis is only nine plays from one game and is by no means definitive. I'll let the film speak for itself and not over generalize, but Shabazz's rebounding (and motor) might be a long term concern for his NBA career. Statistically, his rebounding numbers are somewhat similar to DeMar DeRozan. DeRozan was a pretty good offensive rebounder and a not so good defensive rebounder, but not quite as bad as Shabazz.

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

High Usage, Go-To Guys Against Syracuse

As a diehard Syracuse fan, I have always wondered how opponents' go-to players perform against the Orange relative to other games and teams. Does the vaunted 2-3 zone really make a difference in that respect? With the help of kenpom.com, I set out to examine whether a significant difference exists between go-to players' performance against Syracuse compared to their seasonal averages. (Go-to consists of a greater than 28% usage rate on the season).

Teams that have a go-to guy are 4-12 and teams without are 5-14 against Syracuse this season. There is hardly any difference in the records of how teams perform with or without a go-to guy, however there is a difference in how those players perform compared to their season averages.

As the above chart indicates, only 5 of the 15 players had an offensive rating above their season average. The average offensive rating of the 15 go-to guys against Syracuse was 95, their season average is 105.5. I believe this 10.5% difference to be significant and representative of these players struggling against the zone applied by the men in Orange.

Findings:

Shooting percentages, points, rebounds and assists decreased - Go-to players simply were not as effective against the zone as they were against other teams. Some factors could include Syracuse's length, physicality, or the heightened competition. Only 8 of the 16 games against go-to players were either Big East teams, or NCAA tournament teams.

Turnovers increased - Whether it was a result of playing a top 15 team in Syracuse, or the zone itself, the high usage guys were more careless with the ball. That extra possession could be the difference between a win or a loss.

Minutes decreased and fouls increased - I am curious as to whether it is in the Orange's game plan to attack the opponents' go-to guy. From a common sense standpoint, this makes perfect sense. Get their best player out of the game, and you don't have to worry about him beating you.

Shooting percentages, points, rebounds and assists decreased - Go-to players simply were not as effective against the zone as they were against other teams. Some factors could include Syracuse's length, physicality, or the heightened competition. Only 8 of the 16 games against go-to players were either Big East teams, or NCAA tournament teams.

Turnovers increased - Whether it was a result of playing a top 15 team in Syracuse, or the zone itself, the high usage guys were more careless with the ball. That extra possession could be the difference between a win or a loss.

Minutes decreased and fouls increased - I am curious as to whether it is in the Orange's game plan to attack the opponents' go-to guy. From a common sense standpoint, this makes perfect sense. Get their best player out of the game, and you don't have to worry about him beating you.

What To Do:

If I were creating a game plan against the Orange, I think you need to get your go-to guy involved early. Being too reliant on the 3 ball is a risky strategy, as this game displays where the 2003 Oklahoma Sooners shot a less than stellar 5-28 from 3 point range in their Elite 8 game. However, to beat the Orange, I think you need to establish the high post, whether it is your go-to guy or someone who can pass and hit the open midrange shot. A scorer and distributor in the high post surrounded by 3 shooters on the perimeter and an athletic big on the baseline could be a recipe for success against Syracuse.

If I were creating a game plan against the Orange, I think you need to get your go-to guy involved early. Being too reliant on the 3 ball is a risky strategy, as this game displays where the 2003 Oklahoma Sooners shot a less than stellar 5-28 from 3 point range in their Elite 8 game. However, to beat the Orange, I think you need to establish the high post, whether it is your go-to guy or someone who can pass and hit the open midrange shot. A scorer and distributor in the high post surrounded by 3 shooters on the perimeter and an athletic big on the baseline could be a recipe for success against Syracuse.

For what this means looking at Syracuse moving forward, the only teams with high usage, go-to players in the East region are Bucknell, Davidson, Illinois and Temple. As a Syracuse fan, I'd be thrilled if they play any of these teams as that means they have made the Sweet 16 and avoid Indiana (Temple), or made the Elite 8 and avoid the higher seeds (Bucknell, Davidson, Illinois).

Final Four Values

The running narrative for the NCAA this season has been all about the parity at the top. Yet here we are in mid March and despite "the field being wide open", everyone is taking Louisville. Now I'm not saying this is a bad idea. Louisville may end up cutting down the nets in Atlanta. However, by picking Louisville you are forcing yourself to have a "near" perfect bracket in order to win your pool. In a standard scoring system, you generally have to get the national champion right to win it all (with an example of an exception being if Butler had won). If you are one of the few people in your pool to take a unique team to win it all, you don't have to be all that great with your earlier picks. With Louisville, however, you're going to have to somehow pick up points on other people with Louisville.

The DIFF column on the right is simply (log 5 final four%) - (ESPN final four%). The thing that jumps out is the "Florida Effect". Not only does Florida shatter the top spot for best value, but they also turn Georgetown and Kansas into bad values. There's a whole bunch of uncertainty surrounding the Gators, but if you trust log 5 (and Vegas) they are nearly a must in your bracket. Miami and Ohio State are the other two that stand out. The conference tournaments have a ridiculous amount of pull on ESPN brackets, or so it seems. Ohio State, Miami, Kansas, and Louisville are all in the top five most picked final four teams (with Indiana) and are coming off conference tournament championships. Syracuse has struggled, but they seem like a much better alternative to Indiana in the East than Miami. Finally, if you decide to go with Pitt in your final four, log 5 says you have an 11.7% chance of taking a commanding lead in your pool.

On ESPN, you can currently look at the percentage of people in the country taking any team to reach any round. I thought it would be interesting to compare the average person's picks to Ken Pomeroy's log 5 projections. This will help determining the "value" of final four picks. If a team's value is especially high, it might be worth it to take the gamble in order to attempt to position yourself better among other Louisville brackets. Obviously the log 5 projections aren't perfect. Thus, I decided to include the Vegas odds that each team reaches the final four in the table too. The Vegas odds weren't actually used in finding value teams, but they can either reinforce (or not) the log 5 rankings.

The DIFF column on the right is simply (log 5 final four%) - (ESPN final four%). The thing that jumps out is the "Florida Effect". Not only does Florida shatter the top spot for best value, but they also turn Georgetown and Kansas into bad values. There's a whole bunch of uncertainty surrounding the Gators, but if you trust log 5 (and Vegas) they are nearly a must in your bracket. Miami and Ohio State are the other two that stand out. The conference tournaments have a ridiculous amount of pull on ESPN brackets, or so it seems. Ohio State, Miami, Kansas, and Louisville are all in the top five most picked final four teams (with Indiana) and are coming off conference tournament championships. Syracuse has struggled, but they seem like a much better alternative to Indiana in the East than Miami. Finally, if you decide to go with Pitt in your final four, log 5 says you have an 11.7% chance of taking a commanding lead in your pool.

Sunday, March 17, 2013

Finding an Upset: Three Pointers

Every year in the NCAA tournament, inferior team beat superior teams. Norfolk State was not a better team than Missouri, they just scored more points over a 40 minute period. The cause behind these upsets is variability. It's no shocking revelation that three point shots increase variability. The three point shot has long been known as a great equalizer.

Underdogs need to increase variability by taking riskier strategies (i.e. shooting three pointers). If each team plays at their average, the favorite will win. Threes do NOT ensure an underdog will play better, but if you're going to go out you might as well go out swinging.

To determine which tournament matchups should have the most variability from a three point shooting perspective, I looked at the percentage of three point attempts taken and allowed for both teams (the favorite and the underdog). 3PA% is different from 3P%. I am not concerned with how often a team makes threes. In one single game that number will be difficult to predict. 3PA%, on the other hand, identifies just how often threes are attempted.

Underdogs need to increase variability by taking riskier strategies (i.e. shooting three pointers). If each team plays at their average, the favorite will win. Threes do NOT ensure an underdog will play better, but if you're going to go out you might as well go out swinging.

To determine which tournament matchups should have the most variability from a three point shooting perspective, I looked at the percentage of three point attempts taken and allowed for both teams (the favorite and the underdog). 3PA% is different from 3P%. I am not concerned with how often a team makes threes. In one single game that number will be difficult to predict. 3PA%, on the other hand, identifies just how often threes are attempted.

Key Takeaways

New Mexico and Florida each rely the most heavily on threes of all the favorites. However, they were fortunate enough to draw opponents that don't rely on them. Florida got one of the most unique teams in the country in Northwestern State. Which leads me to my next point...

Northwestern State is an interesting basketball team. Not only do they play at the fastest pace of any team in the country, but they also don't rely on the three at all. They don't take many and they don't let their opponents take many either.

Miami and Georgetown may be the "best" bets at becoming this year's Duke and Missouri. That would make Pacific and Florida Gulf Coast this year's Norfolk St. and Lehigh. I put best in quotes, because obviously all the games we are dealing with in this analysis are long shots. However, the numbers say that Miami and Georgetown are still relatively more likely to have an off night than others top teams.

Valpo and Davidson may want to consider changing up their defenses. Marquette and Michigan State rarely take threes on the offensive end. Coincidentally, Valpo and Davidson rarely allow threes on the defensive end. However, both Marquette and MSU shoot over 50% from two. If the two underdogs want a better shot at reaching the round of 32, changing their normally great defensive strategy might be a good idea.

Saturday, March 16, 2013

The Selection Committee's Tendencies

Tomorrow is selection Sunday, the day bracketology ceases to matter. Personally, I have never really been into dissecting resumes for the bubble teams. Still, I decided to take a look at some of the committee's tendencies between 2006-2012. I think this information is probably more interesting than insightful, as the committee's decisions have a human element to them that are constantly changing.

First, I went to bracketmatrix.com to determine the bubble teams from the past seven years. Bracket Matrix compiles the bracketology of all sites on the internet into one. I decided that if a team was picked in the field on more than 5% of all brackets but less than 95% of all brackets, then they were a bubble team. There were a few exceptions to the rule, but I think it was good enough. 72 teams fit this criteria over the seven years of data.

The first thing I wanted to do was look at the committee's reliance on RPI. I took the average RPI of bubble teams that received bids and the average RPI of bubble teams that did NOT receive bids for each year:

The graph shows that in recent years, the difference in the RPIs of the teams in and out have been very significant. This is a tricky graph to interpret and I don't necessarily think the committee has become more reliant on RPI (as the graph seems to indicate). In 2006 and 2007, teams from conferences like the Missouri Valley had figured out the RPI formula. They were scheduling games to maximize their RPI and naturally not all of them could get in. Still, the graph is a bit concerning for proponents of a reality based selection process.

Next I wanted to look at the biggest surprises according to bracketologists. Basically, which teams have bracketologist been the most wrong on throughout the year?

2006 appears to be the worst year in bracketology history. Only one of 23 people had Air Force and Utah State in the field and yet both got in. In recent years many sites are now doing bracketology, and I believe there has been an increase in both quantity and quality. I wasn't surprised to see a Seth Greenberg Virginia Tech team in the biggest snubs. 87 of 89 bracketologists had the Hokies in the tournament in 2011 despite an RPI of 62.

Next, let's look at the biggest surprises based on RPI:

Notice the conference RPIs for these teams. The snubs were almost all in weaker conferences than the most surprising bids. USC was the worst team according to RPI to get a bid in 2011. All of the RPI snubs are from 2006-2008. This makes sense based on the results of the first graph.

I can't wait for the bubble discussion to end and the actual NCAA tournament analysis to begin. However, I haven't seen much research done on the recent history of the selection committee and thought this could shed some light on that.

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Summit League Championship Preview

Tonight in the battle for the Dakotas, Nate Wolters will attempt to get back to the NCAA tournament one more time for his senior season. The 24-8 North Dakota State Bison stand in his way. Both teams are dominant on one side of the ball. SDSU is ranked first in the Summit League in offensive efficiency, while NDSU is ranked first in the Summit League in defensive efficiency. The teams split their two regular season meetings this year.

We knew to expect big things from Nate Wolters and his team this season, but NDSU has been a big surprise. Defense has been the key to the Bison's success and it has been very Bucknell-ian. They don't create many turnovers, but they make you shoot a poor percentage and then hold you to one shot (rebound). Below is a look at their defensive FG% at the rim, using hoop-math's numbers:

We knew to expect big things from Nate Wolters and his team this season, but NDSU has been a big surprise. Defense has been the key to the Bison's success and it has been very Bucknell-ian. They don't create many turnovers, but they make you shoot a poor percentage and then hold you to one shot (rebound). Below is a look at their defensive FG% at the rim, using hoop-math's numbers:

NDSU ranks number 8 in the country at defending shots at the rim. These shots have been found to be much more controllable (from a defensive perspective) than three pointers. NDSU opponent's have shot 32.3% from three this season (91st in the country). The table below summarizes NDSU's FG% defense:

It's no secret that mid-range jumpers are not an efficient way to score in basketball. Ohio State leads the nation in opponent's two point jumper field goal percentage at 27%, while Portland is last at 45%. So NDSU is above average in relation to the rest of the NCAA. The 1.04 points per shot at the rim seems high compared to the other two shot types, but is nearly as good as it gets for NCAA teams.

Now that we have some background on NDSU's defense, let's take a look at the same analysis but for South Dakota State's offense:

South Dakota State has been about average for NCAA teams at the rim this season, and they have actually shot the same percentage from three as they have on two point jumpers. Obviously, these shooting percentages are not independent of each other. For instance, taking a pull up jumper may force the defense to play tighter and thus make it easier to get to the rim. Making threes stretches the defense and shots around the hoop make a defense collapse inside.

We know that defenses have a larger effect on two pointers than three pointers. However, I'm not sure exactly how much influence the offense has versus the defense. For simplicity, let's say that on any two point shot the offense and defense are equally important. So we can simply average NDSU's defensive FG% and SDSU's offensive FG% together to get an expected FG%. Let's also say (arbitrarily, I want to look more into this in the future) that the offense accounts for 75% of 3P% and the defense the other 25%. Using this, the table below shows SDSU's expected FG% by shot location in tonight's game:

South Dakota State has four very capable three point shooter in Nate Wolters (39%), Jordan Dykstra (44%), Brayden Carlson (34%), and Chad White (44%). The Jackrabbits should not be afraid to let it fly from downtown tonight. A semi-contested three from a great shooting team like SDSU is probably better than testing NDSU's great interior defense.

Friday, March 8, 2013

Minnesota and Rebounds: The Art of Cherry Picking

Last month, I looked at Bucknell and turnovers in college basketball strategy. Another interesting team in the 2013 season has been Tubby Smith's Minnesota team. The Golden Gophers rolled through non conference play, but are just 8-9 in the Big Ten. Despite the struggles, Minnesota is still 16th in efficiency in the country largely due to a ridiculous offensive rebounding percentage.

Minnesota ranks first in the OReb% by a wide margin and just 239th in DReb%. Offensive and defensive rebounding aren't exactly the same skill by any means, but it doesn't make sense that a team would be so far off in the two categories. Instead, I think that the large difference is more a product of the coach's system. Here are the two schematic possibilities for Minneosta's differential.

Minnesota ranks first in the OReb% by a wide margin and just 239th in DReb%. Offensive and defensive rebounding aren't exactly the same skill by any means, but it doesn't make sense that a team would be so far off in the two categories. Instead, I think that the large difference is more a product of the coach's system. Here are the two schematic possibilities for Minneosta's differential.

- Cherry picking - Minnesota is great at rebounding, but they decide to cherry pick (get out in transition) instead of having everyone defensive rebound.

- Allowing cherry picking - Minnesota is not quite as good at rebounding as their OReb% indicates, but they decide to crash the glass relentlessly on offense instead of worrying about transition defense.

The point here is that there is a natural trade-off between rebounding and transition plays.

To further examine this, I first looked at teams with the biggest differentials between offensive and defensive rebounding. To do this, I took the z-score of each, meaning I found how far away a team's OReb% and DReb% are away from the NCAA averages.

The 10 teams on the left are all Minnesota-like. They are much better at offensive rebounding than defensive rebounding. This means we would expect a much higher number of transition players per game than the teams on the right. The teams on the right are conservative when it comes to rebounding (notice Bucknell again). They get back on defense instead of going for offensive rebounds and box out instead of cherry picking. In both cases, the two strategies by the teams on the right limit plays in transition.

I decided to put this theory to the test using hoop-math.com. Using the data from that site, we can see how often these teams both go in transition on offense and allow transition plays on defense. I did this by looking at the percentage of times a team shoots in 10 seconds off missed shots versus the percentage of times a team shoots in 11-35 seconds into the shot clock off missed shots.

The table above illustrates the trade-off between cherry picking and transition. The teams on the left (the cherry pickers) are in transition 42% of the time and allow transition 41% of the time. The teams on the right (the conservatives) are only in transition 32% of the time and allow transition only 35% of the time.

To me, three things particularly stick out about individual teams from the tables above:

- Minnesota is a weird team. It looks like the Golden Gophers are really just that good at offensive rebounding. I expected them to allow an extremely high percentage of transition plays due to crashing the boards, but it was actually the lowest of the top 10 teams at 36%.

- Northwestern St. is the biggest cherry picker in the country. I haven't watched film, but the stats show that Northwestern St. takes a shot within 10 seconds of getting a defensive rebound 58% of the time. This was by far the highest percentage and might be a reason why Northwestern St. is the second best team in the Southland.

- Bucknell ran a fast break once, just to see what it felt like. Yes, I think Bucknell is the most interesting team in the NCAA. Dave Paulsen's squad focuses on boxing out and holding teams to one shot. They only get out in transition on 14% of missed shots (not a typo).

For those of you statistically inclined, here are the scatter plots of the cherry pickers and non cherry pickers. You can see the r-squared values and how big of an outlier Minnesota is in all of this. Removing Minnesota increased correlation tremendously.

Cherry Pickers:

Conservatives:

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

Quantifying Carrick Felix's Defense

Arizona State, picked to finish 11th in the Pac-12 preseason poll, has been a pleasant surprise this year. Currently they are right on the outside looking in at the bubble, but just about no one thought they would be in this position entering the season. Last month, I received an email from Arizona State's assistant coach Eric Musselman. In the email, he told me to check out Carrick Felix's "amazing" defense this season for the Sun Devils. Since then, he has also been quoted on the same topic in this article. Musselman said of Felix, "He’s got to be one of the top five defenders in all of college basketball." Naturally, I decided to try and quantify Felix's defense to dig deeper.

To look at Felix's defense, I decided to just look at Pac-12 games. Generally, ASU has used Felix to guard a top scorer. Felix's versatility is a tremendous advantage here, as he has guarded point guards, shooting guards, small forwards, and power forwards. I wanted to find conference games where Felix guarded just one player for a full game. Then, I could compare the player he guarded's game stats to season averages to get the "Felix Effect". I realize that this method has some limitations. First, the goal of defense is not solely to stop your man. Instead, teams tend to have a defensive philosophy rooted in help principles. Also, there are many circumstances where players stop guarding their assignment over the course of a game. The two most common are transition plays (where the primary goal is to stop the ball) and switches due to screens. Regardless, I identified nine conference games where I determined that Felix primarily guarded one man for nearly (if not all) of the game. The following is a graph of these nine instances. The head of the player Felix guarded represents that player's season ORtg, while Felix's head represents that player's game ORtg. When Felix's head is higher, it means he was "bad" on defense. When Felix's head is lower, it means he was "good" on defense.

As you can see, Felix started the year out with two great games against Andre Roberson (Colorado) and E.J. Singler (Oregon). The only player to significantly get the best of him in conference play has been Mike Ladd of Washington State. In total, Felix has held six under their average ORtg and three over their average ORtg.

The above table shows Felix's defense in more detail. Negative numbers are a good thing from Felix's perspective (hence the green formatting). On average, Felix has lowered a player's offensive rating by about seven points per 100 possessions. We can also see that although Ladd was very efficient in his game against Arizona State, his usage was lower than normal. A defender's ability to affect three point percentage has been heavily scrutinized, so we should probably take those percentages with a grain of salt. However, I fully agree with the numbers concerning free throw attempts. I thought Felix did a great job of not trying to do too much on defense and avoiding fouls. The numbers do say that Felix has had a tendency of not letting players get to the line as much as they are used to.

I wanted to take a look at Victor Oladipo, who is regarded by many as the best defender in the country. Tom Crean's usage of zone defense, however, complicated matters. I was only able to identify five conference games where Oladipo spent the vast majority of his time on one offensive player. Those games are below:

To look at Felix's defense, I decided to just look at Pac-12 games. Generally, ASU has used Felix to guard a top scorer. Felix's versatility is a tremendous advantage here, as he has guarded point guards, shooting guards, small forwards, and power forwards. I wanted to find conference games where Felix guarded just one player for a full game. Then, I could compare the player he guarded's game stats to season averages to get the "Felix Effect". I realize that this method has some limitations. First, the goal of defense is not solely to stop your man. Instead, teams tend to have a defensive philosophy rooted in help principles. Also, there are many circumstances where players stop guarding their assignment over the course of a game. The two most common are transition plays (where the primary goal is to stop the ball) and switches due to screens. Regardless, I identified nine conference games where I determined that Felix primarily guarded one man for nearly (if not all) of the game. The following is a graph of these nine instances. The head of the player Felix guarded represents that player's season ORtg, while Felix's head represents that player's game ORtg. When Felix's head is higher, it means he was "bad" on defense. When Felix's head is lower, it means he was "good" on defense.

As you can see, Felix started the year out with two great games against Andre Roberson (Colorado) and E.J. Singler (Oregon). The only player to significantly get the best of him in conference play has been Mike Ladd of Washington State. In total, Felix has held six under their average ORtg and three over their average ORtg.

The above table shows Felix's defense in more detail. Negative numbers are a good thing from Felix's perspective (hence the green formatting). On average, Felix has lowered a player's offensive rating by about seven points per 100 possessions. We can also see that although Ladd was very efficient in his game against Arizona State, his usage was lower than normal. A defender's ability to affect three point percentage has been heavily scrutinized, so we should probably take those percentages with a grain of salt. However, I fully agree with the numbers concerning free throw attempts. I thought Felix did a great job of not trying to do too much on defense and avoiding fouls. The numbers do say that Felix has had a tendency of not letting players get to the line as much as they are used to.

I wanted to take a look at Victor Oladipo, who is regarded by many as the best defender in the country. Tom Crean's usage of zone defense, however, complicated matters. I was only able to identify five conference games where Oladipo spent the vast majority of his time on one offensive player. Those games are below:

When watching film, it's easy to tell the difference in defensive style between Felix and Oladipo. The latter is very agressive, ranking 20th in the country in steal percentage and averaging 3.6 fouls per 40 minutes. it's hard to really take anything from this small of a sample size, but I was surprised that offensive players have gone at Oladipo. Ryan Evans was the only player who was used on offense less than normal against Indiana.

It's no secret that defensive statistics are far behind offensive statistics. One of the biggest talking points at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference last weekend was the use of new technology to better measure defense. This is especially true for the college game, where we don't have much beyond blocks and steals. I will be the first to say that the best way to judge a player's defense is to watch film. Clearly, Felix's defensive prowess is easily spotted by watching Arizona State play. My goal was to back up the film with numbers. Although the method has some flaws, I think combined with the eye it can give a better total picture of a player's defensive performance.

Monday, March 4, 2013

End of Game Execution

Over the weekend, I tweeted about late game execution in the NBA versus the NCAA. It seemed like this weekend especially, coaches were unable to help their teams execute down the stretch to win close games. We saw this in the Michigan-Michigan State game, but also in many games across the country. The two I picked out were both games tied at the end of regulation with the shot clock off. In these games, Villanova and Northern Arizona were unable to get a solid shot off and both games went into overtime.

In the NBA, the Nuggets beat the Thunder this weekend on a Ty Lawson buzzer beater. I also remembered a play in a Spurs-Cavs game from a few weeks ago where the Spurs were equally as effective in late game execution getting an open Kawhi Leonard three for the win.

I broke down these plays to get a look at what NCAA coaches are doing wrong. In Sunday's Villanova-Pittsburgh game, Jay Wright drew up a high pick and roll for Ryan Arcidiacono. The same type of play the Spurs ran for Tony Parker. Take a look at the spacing for the Spurs compared to Villanova.

The Spurs leave the paint completely open and surround the arc with three point shooters. The three Cavs players not directly involved in the pick and roll have to respect the player they are guarding and can't help on Parker. When Parker gets into the lane, Dion Waiters is forced to make a decision to either stop the ball or stop Kawhi Leonard in the corner. He really didn't do either, and Leonard nailed the three.

On the other hand, Arcidiacono has nowhere to go for Villanova. He is driving hard left right into the Pittsburgh defender on the block. The play had very little chance from the start of getting a good look.

Northern Arizona had similar spacing problems in their end of game play against Weber State. They elected not to take a timeout and drove towards the hoop, but right into a congested area.

Below are videos comparing the end of game execution for the two NCAA teams and the two NBA teams. The videos are annotated and are self-explanatory, but you can clearly see that NBA teams are much better prepared for theses types of the situations. The Nuggets play may have impressed me the most, because they not only set a ball screen, but they also set a clever screen on Durant who was the hedger defending the pick and roll. Sefolosha recognized the play (possibly from scouting) and did a great job of helping, but the Thunder had to perfectly defend the play in order to stop it. See the videos below:

In the NBA, the Nuggets beat the Thunder this weekend on a Ty Lawson buzzer beater. I also remembered a play in a Spurs-Cavs game from a few weeks ago where the Spurs were equally as effective in late game execution getting an open Kawhi Leonard three for the win.

I broke down these plays to get a look at what NCAA coaches are doing wrong. In Sunday's Villanova-Pittsburgh game, Jay Wright drew up a high pick and roll for Ryan Arcidiacono. The same type of play the Spurs ran for Tony Parker. Take a look at the spacing for the Spurs compared to Villanova.

The Spurs leave the paint completely open and surround the arc with three point shooters. The three Cavs players not directly involved in the pick and roll have to respect the player they are guarding and can't help on Parker. When Parker gets into the lane, Dion Waiters is forced to make a decision to either stop the ball or stop Kawhi Leonard in the corner. He really didn't do either, and Leonard nailed the three.

On the other hand, Arcidiacono has nowhere to go for Villanova. He is driving hard left right into the Pittsburgh defender on the block. The play had very little chance from the start of getting a good look.

Northern Arizona had similar spacing problems in their end of game play against Weber State. They elected not to take a timeout and drove towards the hoop, but right into a congested area.

Below are videos comparing the end of game execution for the two NCAA teams and the two NBA teams. The videos are annotated and are self-explanatory, but you can clearly see that NBA teams are much better prepared for theses types of the situations. The Nuggets play may have impressed me the most, because they not only set a ball screen, but they also set a clever screen on Durant who was the hedger defending the pick and roll. Sefolosha recognized the play (possibly from scouting) and did a great job of helping, but the Thunder had to perfectly defend the play in order to stop it. See the videos below:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)